Regardless of where you stand on the political spectrum, I think that most of us could agree that a film charting the life of Ronald Reagan from his days as an amiably wooden B-movie star to the leader of the free world and his political development from a New Deal Democrat to the icon of the conservative movement (even if that particular movement would most likely reject his policies today) has the potential to be an interesting and engrossing biopic, one that potentially use him as a way of examining the American experience of the 20th century. And yet, even his most vociferous detractors may find themselves wondering what he could have done to deserve a film like Reagan, a long-on-the-shelf biopic from director Sean McNamara (whose oeuvre includes the likes of Bratz, Soul Surfer and more direct-to-video installments in the apparently long-running Baby Geniuses franchise than I knew even existed) that offers more unintentional laughs than insights and which lays on its central thesis—that Reagan was essentially ordained by God in order to defeat communism and all it entailed—so thick that the retinas of many viewers may become detached from all the eye-rolling to come. There are some points where it almost feels like a spoof trailer that was inexplicably transformed into a full feature.

The film tries, over the course of 138 minutes, to cover Reagan’s life from his childhood in Eureka, Illinois to his days in the White House in the 80s. This makes sense, I suppose, but what doesn’t make sense is the modern-day framing device that Howard Klausner’s screenplay deploys in which fictional KGB agent Victor Novikov (Jon Voight) is visited by an ambitious young Russian agent (Alex Sparrow) who wants to know why the glory that was the U.S.S.R. ultimately failed. Not only does Novikov ascribe it entirely to Reagan, he reveals that many years before, he was the only one who recognized just how powerful of a threat he would one day become. As biopic framing devices go, this one may not be quite as lazy, cloddish and unenlightening as the one between the aging Charles Chaplin and his book editor in Chaplin, but it comes really close to that dubious mark.

As regaled by Novikov, we see Reagan as a bland movie star who begins to find his calling trying to weed out communist influence in Hollywood via the unions while first wife Jane Wyman (Mena Suvari) wishes he would just stop talking about politics. After she gets kicked to the curb, she is replaced by Nancy Davis (Penelope Ann Miller), who becomes the great love of his life and who encourages him to fully dip his toe into politics, first as governor of California and then by running for the presidency. Once he achieves the latter, he is hardly in office for a couple of months when he narrowly survives an assassination attempt (one the film implies was orchestrated by the KGB). After pulling through, he finds himself tirelessly working to fight the scourge that is communism until the moment when he demands that Soviet premier Gorbachev tear down the Berlin Wall and let freedom reign.

Again, a Reagan biopic is not necessarily a bad idea but this one is practically a primer on how not to do one effectively—the whole film feels like the cinematic equivalent of what might result if a kid put off his oral report for junior high until the last minute and basically offered up a thinly rewritten version of his Wikipedia page. Many events are covered but only on the most basic and-then-this-happened surface level—the film is almost shockingly in its utter lack of curiosity or interest when it comes to exploring what any of them might actually mean other than in the most superficial of terms. While I guess the film deserves some slight credit for devoting a couple of minutes to the Iran-Contra scandal (if only to show Reagan nobly taking the eventual blame despite the insinuation that it was everyone else’s fault but his), many contentious aspects of his life are either ignored completely or reduced to either a brief visual mention in a montage (including the only reference to the AIDS epidemic and his administration’s catastrophic lack of response) or a pithy one-liner. In one of the most obnoxious moments, we see him teasing silent student protestors in 1969 by going “Shhh” to them, a move that inspires delighted laughter from those very same protestors—alas, it doesn’t show if they were laughing when Reagan, in real life, sent in the National Guard to crack their heads a couple of days later.

If that sounds clunky, it is par for the course for a film where everything is depicted in the most one-dimensional manner imaginable. Reagan, of course, is literally deified the moment he is baptized (with the preacher played, perhaps inevitably, by Kevin Sorbo) and all throughout, he is constantly remarking or being reminded about how he serves God, though it doesn’t really have much to say about his faith other than basic lip-service. His enemies—including communism, unions and Democrats—are all heartless monsters who are trying, either deliberately or unintentionally, to destroy America and let the Red Menace reign supreme. There are times when the film goes beyond hagiography into flat-out idolatry which is underscored even further by the consistently clumsy filmmaking choices from McNamara, who tries to do things the way Oliver Stone might have (such as staging Reagan’s assassination attempt by blending together actual footage of the event with a recreation) but somehow gets it all messed up. There are SNL skits from the Reagan era that have a better and more nuanced fix on who he was and what he meant to people and in those cases, at least the laughs were intentional.

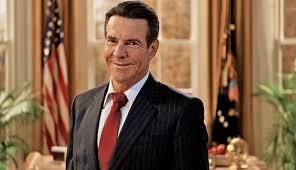

What mild entertainment value there is to glean from Reagan comes from the sight of seeming a number of familiar faces trying to imitate other famous faces, often under loads of makeup and rarely with any success. As Reagan, Dennis Quaid does manage to at times deploy his own innate charm to suggest Reagan’s engagingly folksy spirit but for the most part, what he delivers is an impersonation instead of a performance and while his take on Reagan’s familiar voice and cadences may be better than you Uncle Otto after three beers, it proves to be eminently forgettable in the end. The performances by Miller and Voight, on the other hand, are ones that you will remember, no matter how hard you may want to forget, due to their sheer cruddiness—Miller plays Nancy as a complete simp throughout while Voight is just chewing every available bit of scenery. As for the supporting players, we get such sights as C. Thomas Howell as Caspar Weinberger, Kevin Dillon as Jack Warner, Robert Davi as Leonid Brezhnev and, perhaps inevitably, Creed singer Scott Stapp as Frank Sinatra—after a while, the only suspense left in the story comes from wondering if the film will somehow figure out a way to shoehorn in Scott Baio as well. (Spoiler Alert—they don’t, though to not allow him a turn as Eugene Hasenfus seems like a missed opportunity.)

There have been worse biopics than Reagan, I suppose—there was Wired, the one that showed the late John Belushi being taken on a guided tour of his life (adjusted to avoid potential lawsuits) by his cab-driving Puerto Rican guardian angel, and the insanely misbegotten Gotti, a film whose idiocies I am still not sure I have fully recovered from seeing. Say what you will about those films, they may be virtually unwatchable but at least they are never boring. Reagan, on the other hand, is more painful to watch because it takes a story that should have worked if placed in the right hands and just makes one botched decision after another. Ironically for a film about a man often described as The Great Communicator for his ability to connect with people, we never get any real sense of what exactly the film wants to say about Reagan, either as a person or as a symbol. All we get with Reagan are a series of disjointed scenes, some familiar quotes (“Honey, I forgot to duck”) and the sense that we are watching a real missed opportunity. Put it this way—even most of the titles from Reagan’s own filmography are better and more insightful than this thing.